A Q&A from Paulig’s and EIT Food’s webinar about the European Commissions’ proposal of a harmonized front-of-pack nutrition label to help consumers make healthier choices.

As part of the European Commission’s strategy for a sustainable food system, a legislative proposal of a harmonized, mandatory, front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL) is underway, with the aim to help consumers make healthier food choices and address the public health burden of diseases of lifestyle.

The event invited decision-maker, researcher, consumer, and industry representatives, to share their knowledge, experience, and expectations around FOPNL and the way forward. The discussion included important considerations such as features of importance, implications for consumers, and company learnings and best practices. As a follow up to the event a comprehensive Q&A is provided here.

The event was organized by Paulig, an international food and beverage company, and EIT Food, Europe’s leading food innovation initiative.

Speakers and panelists responding to the Q&A

The Q&A addresses questions asked by the viewers to the event. The following speakers and panelists are responding in this document. For the full list of speakers and panelists see the Webinar Summary.

- Els de Groene, PhD, Global Head Diet & Health Advocacy, Unilever

- Karin Jonsson, PhD, Sustainability Program Manager, Nutrition & Food Health, Paulig

- Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC (European Consumer Organization)

- Herbert Smorenburg, PhD, Managing Director, Choices International Foundation

- Bettina Julin, PhD Nutritionist, the Swedish Food Agency

- Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

Questions & Answers

Q: What exactly is the current situation of the mandatory front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL) legislation to be proposed by the EC? Is the deviation among member states being solved or still hard to be agreed?

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“Following the “Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy, and environmentally-friendly food system” in May 2020, the Commission’s Inception Impact Assessment of December 2020 put forward four options for harmonized FOPNL: nutrient-specific labels – numerical (e.g. Nutrinform Battery); nutrient-specific labels – colour-coded (e.g. Multiple Traffic Light); summary labels – endorsement logos (e.g. the Keyhole); summary labels – graded indicators (e.g. Nutri-Score). More recently, the Commission has made informal statements indicating that all options remain on the table but that there is preference for evaluative schemes even if a specific scheme has not been identified. Much work remains to ensure that only an effective, evidence-based scheme is adopted. It has been reported in media that the initial deadline for the Commission to release the proposal has been pushed back from Q4 2022 to Q2 2023.”

Q: How firm should the criteria for labeling be for determining a product's status, is the goal to completely prevent purchases of e.g. chocolate or ready-to-eat meals?

Els de Groene, PhD, Global Head Diet & Health Advocacy, Unilever

“This is undesirable and not realistic. We cannot dictate what consumers buy and eat; we can guide them in choosing healthier options. There are no healthy and unhealthy products but there are healthy/unhealthy diets. Every product can fit in a healthy diet as long as it is consumed in an appropriate portion size and appropriate frequency of consumption. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling should help consumers making healthier choices in each product category.”

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“The goal of front-of-pack nutrition labelling is not to ban or ‘force’ consumers to not eat certain foods. It is simply an information tool which, when well-designed, can help shoppers make more informed and healthier choices if they wish. Where the Nutri-Score has already been rolled out, consumers can and indeed do still purchase foods which receive ‘D’ or ‘E’ scores. What the Nutri-Score allows consumers to do is glean, at-a-glance, information about the nutritional composition of a range of foods. Given the critical rates of overweight and obesity amongst the EU populations, for adults and children alike, a front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL) like the Nutri-Score can help consumers to consider consuming foods with worse scores in smaller portions and less frequently.”

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“It is possible to identify food which are more healthy and less healthy. However, we should be focusing on what the objectives of FOPNLs are. Graded, summary evaluative FOPNLs like Nutri-Score help provide consumers with information, in relative terms, that allows them, at a glance, to compare easily the nutritional quality of foods. In reality, consumers make relevant comparisons, particularly on the same shelves of supermarkets, e.g., consumers can compare ratings of different cereal brands.”

Herbert Smorenburg, PhD, Managing Director, Choices International Foundation

“I agree with the previous panelists that the goal is not to completely prevent consumption of less healthy foods and drinks. However, in order to improve diets, consumption of less healthy products needs to be reduced (frequency and portions) and the consumption of healthier products needs to be promoted. Labelling, reformulation, marketing restrictions, nutrition and health claim regulations, financial policies (including subsidies and taxes) that are consistently based on a good nutrient profiling system will help to do so.”

Q: Is it not a catch 22 to aim for a “keep it simple” type of front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL) framework for a complex topic as nutrition and health?

Karin Jonsson, PhD, Sustainability Program Manager, Nutrition & Food Health, Paulig

“We see it as a possibility to provide independent, simplified guidance for the consumers. There are already several (‘simple’) FOPNLs on the market. By harmonizing the use of nutrition labels, we see benefits for both consumers and companies regarding clarity, trustworthiness, and joint forces for improvement of the label of choice. Nutrients most important for health are well established, the trick is to evaluate products and product categories as fair as possible, expressing the result in a clear and simple way for the consumers. As a food manufacturer, we can contribute to making a simple FOPNL as representative as possible of the nutritional quality of our products. We encourage our peers to be active and supportive in the dialogue, and the Commission to value and facilitate our support.”

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“Many factors influence the effectiveness of FOPNLs in shaping healthier diets. This includes consumers’ attention, awareness, liking, acceptance, understanding, and drawing of correct health inferences from a FOPNL. Various other factors also include the extent to which FOPNL inform purchase decisions and the potential for FOPNL to lead to reformulation. Extrinsic and intrinsic factors affect labels, e.g., consumer motivation and design, format, and placement of the FOPNL. A mass of evidence shows that simplified, evaluative FOPNL, which provides consumers with guidance, is most effective to help inform them and lead to healthier choices. If consumers want more detailed information, they can also read the back-of-pack nutrition declaration in conjunction with the ingredients list.”

Herbert Smorenburg, PhD, Managing Director, Choices International Foundation

“It is not simple at all to assess the healthiness of products, but that does not mean that this should not be done by an independent, scientific methodology. To translate this then to ‘simple’ consumer information means that the labelling is well understood by consumers, it is implemented consistently and mandatory, and other nutrition policies are consistent with the front-of-pack nutrition labelling.”

Q: EU also protects traditional products such as sausages and ham. How can you still protect and promote those traditional products if, in instance, the multi-score scale will say that the product is unhealthy

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“Firstly, it is important to underline that just because a food has a traditional quality mark does not mean that it is necessarily going to score badly with the Nutri-Score. In fact, our French member ‘UFC Que Choisir’ recently conducted a study of 588 traditional foods in France and found that, in fact, the majority (62%) did not receive the worst scores (‘D’ or ‘E’). Traditional foods are not limited to cured hams and salty cheese but include many foods with nutritional compositions which result in ‘good’ scores.

Secondly, the Nutri-Score is simply a translation of the nutritional information on the back of the pack. When a food, traditional or otherwise, receives a low score, it is simply because the levels of nutrients to limit such as saturated fat, salt or sugar are high in that particular product. It is right that the consumer should be aware of that before they purchase.”

Q: While evidence and experts' views here tend to support the proposal of making Nutri-Score scheme mandatory, our study showed that the majority of Belgian and French consumers do agree that Nutri-Score label should appear on all products regardless of their healthiness, likely also reported in many other studies. While the major criticism in the last EU meetings was related to over-simplification (which is somehow the rationale of a front-of-pack label) what exactly is the reason/strongest counter-argument at the EU level that hinders the implementation of Nutri-Score?

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“Amongst EU Member States, civil society, medical and health organizations, consumer groups and academics, Nutri-Score is the preferred scheme. It has the most support by the food industry also. Even the WHO International Agency for Cancer Research has recommended Nutri-Score. This is not surprising as over 60 international peer-reviewed studied have supported the adoption of Nutri-Score. There are two main types of opposition to Nutri-Score. One is the loyalty of some Member States to scheme they have been using for many years. The greatest obstacle is the opposition of a part of industry and a few Member States who do not want food products labelled with D and E. This is mainly an economic opposition because of the huge profit generated by nutritionally poor food. This part of industry is engaging in strong lobbying and financing to discredit Nutri-Score. Other companies, however, are following the science – the Commission and Member States needs to listen to the stakeholders who are arguing for proposals in favor of consumer informed choice and health.”

Q: As we know, Nutri-Score is a highly discussed topic as part of front-of-pack nutrition labelling, possibly mandatory. Currently, products that are not recommended to consume in high quantities according to national dietary authorities and guidelines have a positive or neutral Nutri-Score label (A, B, or C) on it. The fact that a product which is not recommended to consume according to dietary guidelines has a positive Nutri-Score (e.g. some snacks and sweets) and therefore actually encourages its consumption. What do you think of this and how to address this?

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“There is often a misconception that the Nutri-Score somehow goes against dietary recommendations or even favors ultra-processed foods. In reality, the opposite is the case: Nutri-Score is very well-aligned with dietary guidelines, including the recommendation to limit the consumption of ultra-processed foods.

Front-of-pack nutrition labelling and dietary guidelines are tools which are different yet complementary. Dietary guidelines can give consumers a general idea of what a healthy diet should look like, while front-of-pack nutrition labels (FOPNLs) give information on individual products, which dietary guidelines clearly cannot. While a dietary guideline may be to consume oily fish twice a week for example, a FOPNL, if well-designed, can help consumers in the supermarket situation to opt for fresh salmon instead of salty cured salmon.

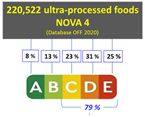

It is important to recall that nutritional composition and level of processing are two separate dimensions of a food. Even though the majority of ultra-processed foods score badly with the Nutri-Score (see below: a database of over 220,000 products found that the large majority – 79%- do not get an A or B), because the Nutri-Score is simply a translation of the back of the pack nutritional information, it is unsurprising that a limited number of ultra-processed foods which contain minimal amounts of fat, sugar or salt may achieve better scores.”

Karin Jonsson, PhD, Sustainability Program Manager, Nutrition & Food Health, Paulig

“Nutri-Score comprises many features identified by the European Commission’s policy report and review by the Joint Research Centre for a well-functioning front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL). However, all labels have strengths and weaknesses, i.e. development areas, Nutri-Score is no exception. Stakeholder engagement is needed to secure fair and responsible judgements of products.

Bringing in ultra-processing as a factor in FOPNL is to make an already complex topic even more complex, not necessarily to the better. The definition of ultra-processing is blunt and inconsistent and can be misleading. Examples are certain single-ingredient foods that may be little processed but contain high amounts of e.g. saturated fat, compared with foods containing multiple healthy components, processed to a high extent but in a way that retains important nutrients and improves their bioavailability.

Nutri-Score is based on well-established nutrients and food groups that are limited or encouraged by dietary guidelines. From a reformulation perspective, according to Paulig, the setup of Nutri-Score works well as a guide in line with dietary recommendations. The five grades allow for comprehensive guidance of different magnitude and of products with different nutritional quality. The algorithm, rather than threshold-levels, provides in our view more freedom and creativity in the development of healthier products, and we see similarities with how dietary risk factors for disease development works: the healthier overall composition of one’s diet, the less importance of single risk factors.”

Herbert Smorenburg, PhD, Managing Director, Choices International Foundation

“Whilst I agree with Emma and Karin that Nutri-Score is well aligned with dietary guidelines and well-established nutrients, I do understand the question that is raised and it has been a key concern of many nutrition experts, for example in the Netherlands (see Dutch nutrition experts criticise Nutri-Score and Evaluation study by the Dutch Health Council). To address these issues, the Scientific Committee of Nutri-Score has adapted the Nutri-Score algorithm for solid foods, and an adaptation for liquids is expected before the end of 2022. Whether these adaptations are sufficient needs to be evaluated.”

Q: To what extent may front-of-pack labelling mislead the consumer? For example, a bottle of extra virgin olive oil will possess possibly a Nutri-Score E. Considering that this monounsaturated fat is one of the healthiest fats for cooking, to what extent could this labelling mislead the consumer?

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“Olive oil has always been amongst the best-scoring fat or oil. It has never scored ‘E’. Currently olive oil scores ‘C’ and, with the recent update of the Nutri-Score algorithm, to take into account the scientific perspective of the 7 different countries officially engaging in Nutri-Score, it will in the future score ‘B’. This means that a consumer wishing to purchase the healthiest fat or oil will always know that olive oil (and other vegetable oils with similar nutritional compositions) is the best choice.”

Herbert Smorenburg, PhD, Managing Director, Choices International Foundation

“This is a good example of where the consumer loses trust in the labelling system. The labelling system needs to be consistent with what is commonly known and understood as healthy and not healthy. A high percentage of alignment with dietary guidelines is not sufficient, a few misalignments may be detrimental for trust in the labelling system.”

Q: To have a Keyhole label, products need to have a very low salt content, below palatability. Is this label unfair towards ready-to-eat meals that might be seasoned in a reasonable level for the meal? Could this confuse consumers that there are no ‘healthy’ ready-to-eat meals?

Bettina Julin, PhD Nutritionist, the Swedish Food Agency

“That the salt threshold for ready-to-eat meals is below palatability should not be assumed as a fact. According to our newly published survey on salt content in lunches, almost half of the meals purchased from grocery stores where within the threshold for salt. In addition, salty taste is a matter of habits. The more salt you eat, the more you will need to obtain the preferred taste. But in only four to five weeks the taste buds can adapt to a lower salt intake.

The Nordic working group for the Keyhole is continuously revising the criteria on a long-term basis, aiming to increase the number of Keyhole labeled products by making it easier for companies to label products, without making the criteria less strict. Ready-to-eat meals may be labeled with the Keyhole and there are labeled products on the market although not as many as several other product categories. To increase Keyhole labeled ready-to-eat meals, the Nordic working group changed the criteria for ready-to-eat meals in the 2021 revision. One of the changes was that the threshold for salt content per portion was removed (but the criteria per 100 g was left unchanged). However, the salt intake in Sweden is too high, like elsewhere in the Nordics. There is strong scientific evidence that a high salt intake increases the risk of high blood pressure, which is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. As a consumer, it is not possible to influence the amount of salt in meals or dishes purchased outside the home. It is therefore important that producers lower the amount of salt in such food and the lowering need to be done in all foods.

With that said, I do not think the label is unfair towards ready-to-eat meals. But, as mentioned during the discussion, no single system is perfect and need continuous review to allow for continuous improvement.”

Q: They keyhole does not include ‘unhealthy categories’, such as snacks and candy, because you do not want to encourage their consumption. But would there not be of value to encourage companies and consumers toward healthier alternatives, such as low- or no-sugar alternatives or snacks with healthy fats, fiber and lower salt content? Now there is instead a problem with snacks marketed as ‘healthy’ that, e.g., contain some lentils but still have very high content of salt and energy.

Bettina Julin, PhD Nutritionist, the Swedish Food Agency

“With an endorsement scheme like the Keyhole is, it is not straight forward which food categories should be able to be labeled. Although the label is to be compared with products belonging to the same food group, people do not always perceive the label in that sense. In fact, when the Keyhole was launched in 1989, there was a possibility to label ice cream with lower amounts of fat and sugar compared to other ice cream products. Our experience is that with such an option, consumers perceived Keyhole labeled ice cream as healthy, which is contradictory in our view even if it is healthier compared to other ice cream.”

Herbert Smorenburg, PhD, Managing Director, Choices International Foundation

“We had the same experience with the positive Choices labelling in the Netherlands. This is one of the reasons why the Choices criteria evolved to a 5-level criteria system, where basic food product groups, which are part of the dietary guidelines, are eligible A or B grade, whereas non-basic products such as snacks and or ice-cream can only score C, D or E. Thus still differentiating but not positioned as healthy.“

Karin Jonsson, PhD, Sustainability Program Manager, Nutrition & Food Health, Paulig

“As a food manufacturer, we see benefits of a model that allows all food categories to be evaluated, having at least the possibility to receive a scoring of good nutritional quality. That snacks or ice-cream etc., must be unhealthy is a misconception; rather the snacking category provides an opportunity for easy access of tasty and healthy products containing high amounts of seeds, nuts, fruit, and/or wholegrain and fibre, and low (enough) amounts of saturated fat, sugar, and salt. In Nutri-Score, snacks are judged by the same criteria as for example bread, which stimulates and guides us toward healthier snacking. Without guidance provided through e.g., a governmentally endorsed front-of-pack nutrition label, each company must set their own arbitrary criteria for ‘healthy’, if even aspiring to do so.”

Q: What is this panel's view on considering a front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL) being the secondary form of consumer communication that is basically reminding the consumer on this topic where primary communications programs are applied through other forms, like Unilever is advising (permanent consumer education), so a sort of mind shift of the role FOPNL could fulfill?

Els de Groene, PhD, Global Head Diet & Health Advocacy, Unilever

“What I meant is that a FOPNL should not be seen as the ‘magic bullet’, alone solving e.g., obesity. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling should be embedded in a broader government programme, including consumer education and continuous communication on healthy diets and lifestyle.”

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“Of course, dietary guidelines are the backbone of national nutritional policies, but it goes without saying that consumers do not have a copy of these recommendations when they do their food shopping. Indeed, even if they did, these guidelines do not give specific recommendations on individual products, which is where a FOPNL can play a role to supplement the information.

While we can and should of course inform consumers about what a healthy diet looks like and which foods we should privilege and which ones we can limit in our diet, it is not enough to simply educate consumers. There are multiple factors which push or pull consumers towards their food purchasing choices and unfortunately, today, the food environments within which we make our decisions are not conducive to making the healthier choice the easier choice.

The EU’s own chief scientists highlight the need to improve food environments – it is no longer enough to focus on ‘consumer choice’ and individual responsibility when subconscious influences all around us shape what we eat.

Just as the causes of the obesity crisis are multi-factorial, so too must be our response to tackle these issues. No one tool can be a ‘silver bullet’, but FOPNL is well-recognized as an effective tool (when well-designed) in helping consumers make more informed and healthier choices in the supermarket.”

Karin Jonsson, PhD, Sustainability Program Manager, Nutrition & Food Health, Paulig

“Referring to the importance of a multifactorial approach, a FOPNL may not only guide ‘consumer choice’ at the store, but a FOPNL may also stimulate companies to reformulate toward healthier products, resulting in an overall improved nutritional quality of products available.”

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“No single intervention is enough. In terms of informing consumers about individual products, there is no measure equal to labelling – no amount of education can tell consumers quickly and relatively figure out the nutritional quality as an evaluative FOPNL. A FOPNL is uniquely able to be seen every time food is bought and most times when it is eaten – no other intervention has this reach. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling is one part of a series of interventions. After a one-off cost by industry, which is not expensive as part of the lifecycle of labelling design, a FOPNL is also incredibly cost-effective. Moreover, lots of studies have shown that mass and individual campaigns are not as effective as FOPNLs. A FOPNL requires the support of education campaigns to ensure consumers fully understand it, but education is not a substitute for a FOPNL.”

Q: Good point from Els: there should be effectiveness studies. But we already know from research that labels are not that effective in changing our behavior. A lot of money and time is spend developing a new label. What is your opinion about a new label in general, taking that all into account?

Els de Groene, PhD, Global Head Diet & Health Advocacy, Unilever

“In general, there is lack of effectiveness studies in real life settings. We miss out on learnings and improving the front-of-pack nutrition labelling (FOPNL) scheme and/or accompanying communication. It comes back to not expect a FOPNL being the magic bullet but part of a bigger nutrition and health program.”

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“As mentioned above, just as the causes of the obesity crisis are multi-factorial, so too must be our response to tackle these issues. No one tool can be a ‘silver bullet’, but a FOPNL is well-recognized as an effective tool (when well-designed) in helping consumers make more informed and healthier choices in the supermarket.

Indeed, the Joint Research Centre in its recent scientific review of front-of-pack nutritional labelling concluded that ‘FOPNLs has the potential to guide consumers towards healthier diets and can stimulate food product reformulation and innovation. Simpler, evaluative, color-coded labels seem better suited in meeting consumers’ information needs in a busy shopping context.

There is a very robust body of independent, peer-reviewed scientific evidence, including real-life supermarket trials, which has demonstrated that the Nutri-Score is the best label at improving consumer understanding and helping them to make healthier food and drink choices. Crucially, the Nutri-Score has also been shown to be the most effective at assisting consumers from lower socio-economic groups to have shopping baskets with lower amounts of fats, salt, and sugar. This is important because these groups tend to be the most at risk of becoming overweight or obese.

The WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) also recently outlined why it supports Nutri-Score.“

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“Often there is a demand for more and more evidence – sometimes opponents will call for so much evidence that no scheme could ever meet this requirement. What we do know is that there is a mass of peer-reviewed, international evidence showing that a FOPNL like Nutri-Score is effective in improving awareness, understanding, encouraging healthier intent, improved trolley outcomes, etc. This holds true for all socioeconomic groups. This has been confirmed by the EU’s Joint Research Centre reviews. As there is scientific consensus grounded in evidence which has now crossed the threshold of sufficient evidence, the only problem is a lack of political will.”

Q: Herbert was requesting from companies to benchmark its products against several front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes, but would that not counteract the very purpose of harmonization?

Herbert Smorenburg, PhD, Managing Director, Choices International Foundation

“I meant to say two things: Firstly, to encourage companies to report against published, independent and science based external benchmarks, not (only) their own. Secondly, that given that each nutrient profiling system is a ‘lens’ on the reality, it may be helpful to assess the reality by looking through different lenses. Nutri-Score and Health Star Rating are both based on the UK Ofcom Nutrient Profiling model and are therefore similar and an ‘across-the-board’ nutrient profiling model with a scoring algorithm; Choices 5-level criteria and the WHO Europe are nutrient profiling models that are product group specific and use pass-or-fail thresholds, and thus are fundamentally different.”

Q: According to Nikhil and Emma, science seem to favor comparisons between 100 gram products, although Els lifted the importance of having portion sizes; is there an approach that is some kind of ‘in-between’ option, taking the best out of both?

Els de Groene, PhD, Global Head Diet & Health Advocacy, Unilever

“An algorithm underlying front-of-pack nutrition labelling based on specific product group criteria, where the role of the diet is taken into account.”

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“Portion sizes are chosen by manufacturers themselves so can often be arbitrarily small which gives a misleading impression. In any case, from a consumer perspective it is crucial that a front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL) is based on a uniform reference amount (per 100 g or per 100 ml) so that consumers can compare easily between products.

A now-abandoned experiment by some food companies to use a portion-based FOPNL with colours showed that even chocolate spreads which are almost entirely full of sugar and saturated fat would not score badly precisely because the label was based on small portions. Moreover, this label was shown in a study to actually increase the portions of less healthy foods selected by consumers.”

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“The only way for consumers to be able to meaningfully compare products is per 100 grams or milliliters. Portion sizes are the easiest way of misleading consumers and erroneously making products look more nutritional. Many products score A or B when calculated using portion size but D or E when using per 100 grams (or ml). This is because manufacturers choose the portion size themselves – a portion size is not legally required to reflect consumption in reality, e.g., one portion is sometimes half a small chocolate bar. The portion size is also difficult to define as it varies depending on age, gender, physical lifestyle, etc.”

Q: Would a front-of-pack nutrition labelling change the standards for the sizes of some of the mandatory components of a label?

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“A front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL) would mean there is potentially less space available for marketing messages to appear on labelling. This is true of all forms of labelling e.g., ingredients, nutritional table, allergens, etc. Labels can be designed to promote manufacturer interests as well as display FOPNL. Indeed, FOPNL size requirements are often determined on the basis of the label size. EU law sets out the minimum sizes for other forms of mandatory labelling (e.g., 1.2 mm font size) and these are unaffected by proposals for FOPNL. It must be recalled that FOPNL appears on the front of packaging, whereas most manufacturers choose to place most other mandatory labelling on the back of packaging.”

Q: I believe the front of the package of every product (principal display unit) is where every company would like to sell their brand and from statistics, consumers make purchases largely based on the brand. Would front-of-pack nutrition labelling minimize that opportunity for producers to boldly sell themselves on the front?

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“Front-of-pack nutrition labelling does not prohibit branding. There are separate but linked proposals on regulating more effectively health and nutrition claims.”

Q: Concerning Emma saying that we missed our chance earlier to harmonize a label, this time we really must act, while Nikhil was saying that if we cannot agree on a model or if we do not have the perfect model, we should not do anything. Can you elaborate on your own and each other’s points?

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“Indeed, we believe that it was a missed opportunity when the Food Information to Consumers Regulation was adopted in 2011 to already introduce a color-coded interpretive front-of-pack nutrition label (FOPNL). Over a decade later we finally have the chance again to provide consumers with a tool which we know they appreciate in the supermarket and can, when well-designed, lead to more informed and healthier choices. That is why it is essential that we do not waste this opportunity and get it right this time. From a consumer perspective this means: an interpretive label, with color codes and based on a uniform reference basis.”

Nikhil Gokani, PhD, Lecturer in Consumer Protection and Public Health Law, University of Essex

“Currently EU law prohibits Member States from making a FOPNL mandatory. In an ideal scenario the EU can and will agree on an effective FOPNL (which the evidence says is Nutri-Score). However, history and current lobbying tells us that this may not be easy. Therefore, what I was saying is that, if the EU cannot agree on a single scheme, it should change the law to allow/require Member States to choose their own effective schemes (based on principles derived from scientific consensus, e.g., per 100 g/ml, evaluative, color coded). This alternative, the ‘back-up’ option, would still help consumers even if it would not be as good in helping all consumers and creating a level playing field.”

Q: What entity would be responsible for overseeing/controlling whether a nutrition label is correct? Would that be a state agency or private third-party companies as is the case with organic certification?

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“Member States are responsible for conducting enforcement checks on food labels.”

Q: From nutrition label to an ‘ecolabel’ (for other aspects of sustainability than nutrition): any advice how to set it up or how better not to try setting it up? E.g., in terms of how to organize the process, engage stakeholders, etc.

Emma Calvert, Senior Food Policy Officer, BEUC

“The World Health Organization has developed a manual for the development and implementation of front-of-pack nutrition labelling (here). This document outlines a five-step approach that countries can follow to develop and implement an evidence-based front-of-pack labelling scheme:

1. Select the specific strategy: what is expected from a front-of-pack nutrient label (FOPNL).

2. Select the type of the FOPNL graphical design.

3. Determine the underlying nutrient profiling system.

4. Define studies to be performed to select the final format.

5. Establish monitoring procedures.

It highlights that interpretive elements are the most useful to consumers as they simplify the information on the back-of-pack.”